Nice guidelines

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng158/evidence/a-ddimer-testing-in-the-diagnosis-of-deep-vein-thrombosis-and-pulmonary-embolism-pdf-8710588334

Social activist, Entrepreneur and Farmer

Author: Lily Guo

Editors: Alyssa Haag, Ian Mannarino, MBA, MD, Kelsey LaFayette, DNP, RN

Illustrator: Jessica Reynolds, MS

Copyeditor: Sadia Zaman, MBBS, BSc

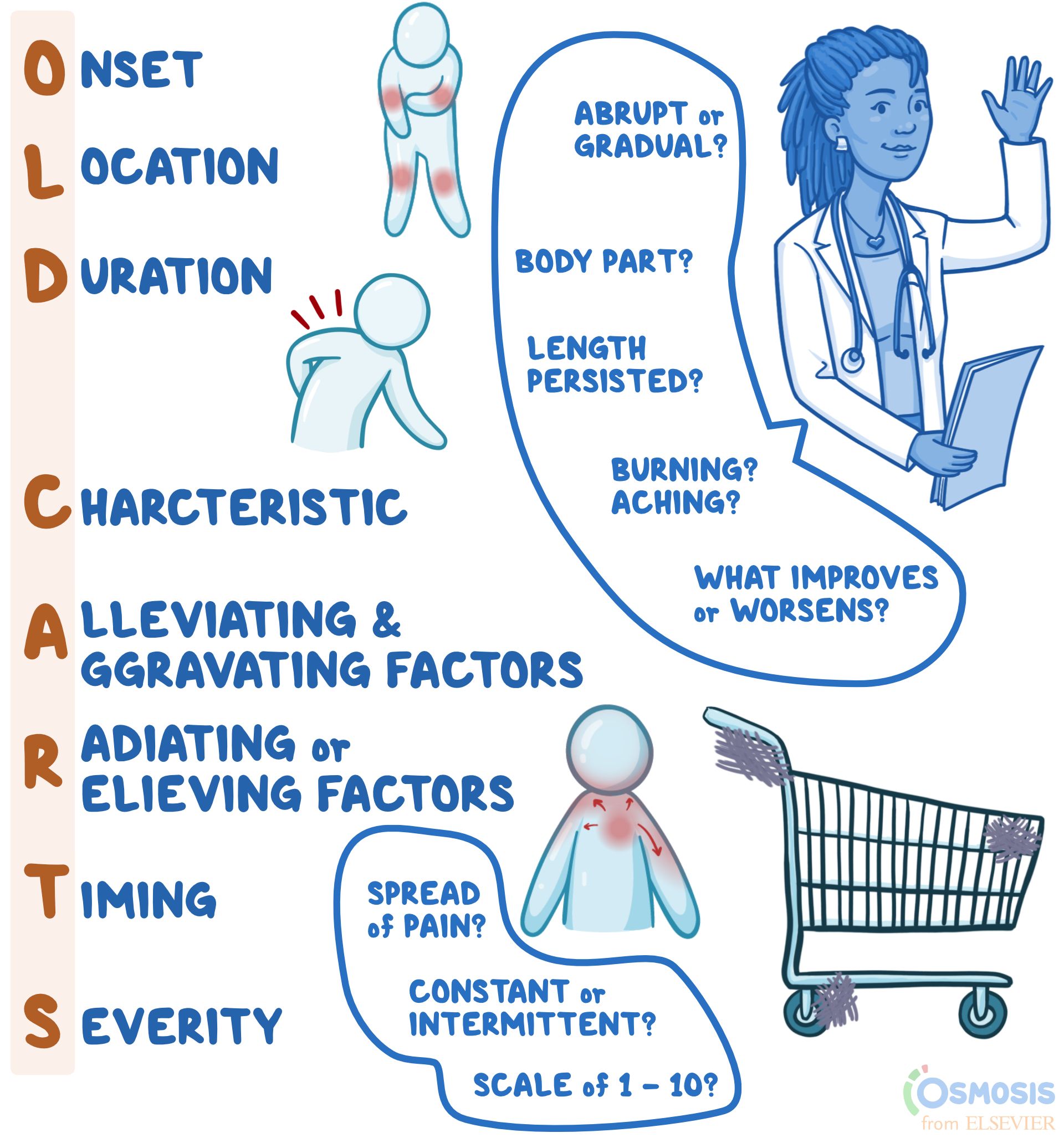

"OLD CARTS" is a mnemonic device that assists clinicians in remembering the pertinent questions to ask while assessing an individual’s present illness. When a person presents to their clinician with complaints of a new or reoccurring medical problem, the clinician may use "OLD CARTS" as a structured guideline and framework from which they will ask questions and collect information before they perform a physical exam. Most commonly, "OLD CARTS" can be utilized for a patient who is experiencing pain, however, this mnemonic can be used as a framework for any presenting symptom.

A history of present illness, abbreviated HPI, refers to the description of an individual’s current health complaint, typically described in chronological order from the onset of their first sign and symptom to the present, defined as the moment they are sitting in front of the clinician. It is a narrative written in full-sentence format by the clinician that provides the necessary information for the clinician to generate differential diagnoses, guide medical-decision making, investigate the problem, and ultimately, provide the proper treatment.

The O in OLD CARTS means onset, indicating when and how the complaint began. For example, the clinician may ask if the pain has been present for hours, days, months, or years as well as if the pain occurs abruptly or gradually.

The “L” in “OLD CARTS” means location. This refers to where the pain is, including which specific body part (e.g., head, arm, leg, abdomen) and if the pain is isolated to one specific area (e.g., headache isolated to one side of the head, or abdominal pain of the right lower quadrant).

The “D” in “OLD CARTS” means duration. This refers to how long or how often the complaint occurs. For example, the pain may last for minutes, hours, or days at a time.

The “C” in “OLD CARTS” means characteristic. The clinician may ask the individual to describe their pain using words such as achy, dull, stabbing, sharp, throbbing, squeezing, itching, or burning.

The “A” in “OLD CARTS” means alleviating and aggravating factors. The individual may be asked if they did anything to help alleviate the pain, such as taking medications or resting. If they did try home remedies, it would be helpful to know if they improved the symptom. The clinician may also ask if anything worsens the pain, such as changing body position, walking up stairs, or eating.

The “R” in “OLD CARTS” means radiation, which refers to whether the pain travels to other parts of the body or whether it is isolated to one region only. “R” in “OLD CARTS” may also refer to relieving factors, or activities or treatments that reduce the pain. The mnemonic may vary slightly depending on the source.

The “T” in “OLD CARTS” means timing. This refers to if the pain is constant and experienced at all times, or if it is intermittent, meaning it comes and goes. If the pain is constant, the clinician might ask if the severity fluctuates throughout the day, which is referred to as waxing and waning pain. Meanwhile, if the symptom is intermittent in frequency, clinicians might ask how many times a week, month, or year it occurs.

The “S” in “OLD CARTS” means severity. For pain specifically, people are typically asked to rank their level of pain from one to ten, with ten being described as the worst pain they have ever experienced. Other questions to help gauge severity can include asking how the complaint interferes with day-to-day life or how bothersome the complaint is to the individual.

“OLD CARTS” is a mnemonic device used by providers to guide their interview of a patient while documenting a history of present illness. The letters stand for onset; location; duration; characteristic; alleviating and aggravating factors; radiation or relieving factors; timing; and severity. What each letter stands for may vary slightly depending on the source of the mnemonic. Onset refers to when the symptom, for example pain, first began and whether it was abrupt or gradual; location refers to the body part(s) affected; duration refers to the length of time the symptoms have persisted; and characteristic refers to the individual’s description of the symptoms (i.e., burning, aching, sharp). Alleviating and aggravating factors are factors that improve or worsen symptoms, respectively; radiation refers to whether there is any spread of pain; timing refers to whether the pain is constant or intermittent; and lastly, severity is typically ranked on a scale of one to ten, with ten being the most severe. When used to guide documentation of an HPI, the mnemonic “OLD CARTS” can make patient evaluation and management more concise and efficient.

Physical Health Assessment: Methods and Steps (theworldbook.org)

The four basic methods or techniques for physical health assessment are:

History taking is the first step of Physical Health Assessment. The general framework for history taking is as follows:

After collecting the health history and before going through the complete head to toe examination, some information or baseline data is collected which is called a general survey.

The general survey includes the person’s weight, height, body build, posture, gait, obvious signs of distress, level of hygiene and grooming, skin integrity, vital signs, oxygen saturation, and the person’s actual age compared and contrasted to the age that the person actually appears like.

For example, does the person appear to be older than his actual age? Does the person appear to be younger than his actual age?

A thorough physical assessment consists of the following: